If you look up the word “theme” in the Oxford Dictionary of English, it is defined as: “an idea that recurs in or pervades a work of art or literature: love and honour are the pivotal themes of the Hornblower books.” If you lookup “theme park” you get: “an amusement park with a unifying setting or idea.” As in Disneyland or The Wizarding World of Harry Potter. Thinking of theme in relation to these theme parks is a good way to understand what the central theme means to a story. To further understand this central theme concept, we can turn to Wikipedia, which has a good summary of the subject:

In contemporary literary studies, a theme is the central topic a text treats. Themes can be divided into two categories: a work’s thematic concept is what readers “think the work is about” and its thematic statement being “what the work says about the subject”.

The most common contemporary understanding of theme is an idea or point that is central to a story, which can often be summed in a single word (e.g. love, death, betrayal). Typical examples of themes of this type are conflict between the individual and society; coming of age; humans in conflict with technology; nostalgia; and the dangers of unchecked ambition. A theme may be exemplified by the actions, utterances, or thoughts of a character in a novel. An example of this would be the theme loneliness in John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, wherein many of the characters seem to be lonely. It may differ from the thesis—the text’s or author’s implied worldview.

A story may have several themes. Themes often explore historically common or cross-culturally recognizable ideas, such as ethical questions, and are usually implied rather than stated explicitly. An example of this would be whether one should live a seemingly better life, at the price of giving up parts of ones humanity, which is a theme in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Along with plot, character, setting, and style, theme is considered one of the components of fiction.

For a novel, movie, or stage play the theme would be the central topic or idea treated by the story, and it should conceptually hold the story together, focus it so that it doesn’t ramble off the rails. How an author accomplishes this is another matter. I’m really big on finding ways to make the elements of story structure actionable. No one actually treats this subject adequately, so I’ve tried to find a way of making it actionable in Story Alchemy. I’ve done this by realizing that the story elements plot, character and theme are not separate entities but indelibly related. Theme is what the central conflict is about. This isn’t an opinion. It is a fact. It focuses the story and keeps it from wandering off topic.

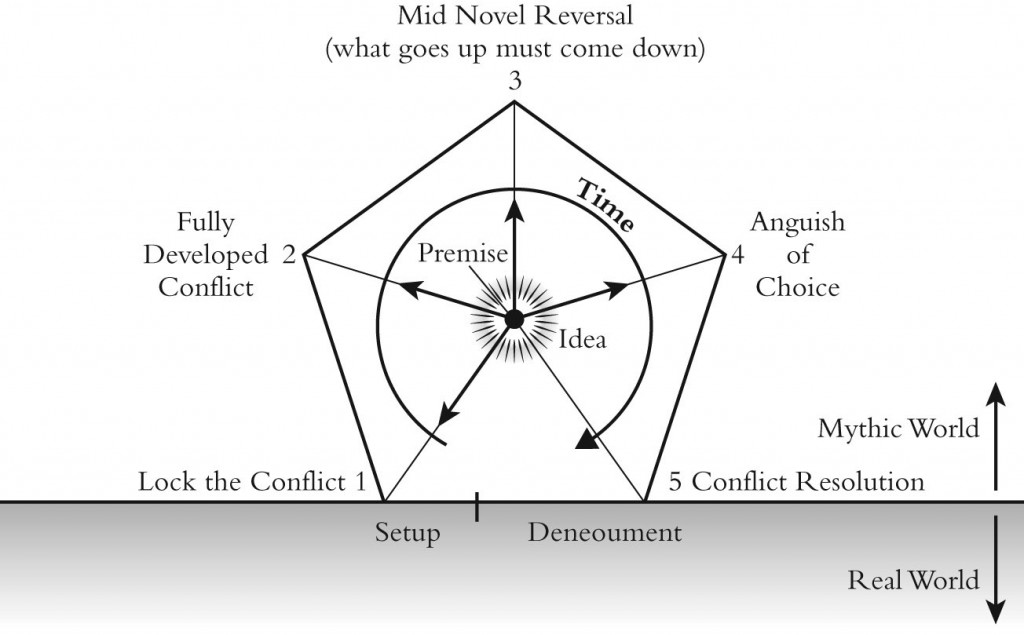

Theme is exposed by the central conflict, and the central conflict is a result of opposing wills, i.e., the protagonist and antagonist. Character, conflict and theme are not separable, and to talk about which comes first is to misunderstand the basic nature of story. This is true not only of the central plot but also of the subplots, which unsurprisingly spring from sub-conflicts. The plot is the evolution of conflict. Conflict has certain attributes, and those attributes are defined in Story Alchemy by the plot pentagon:

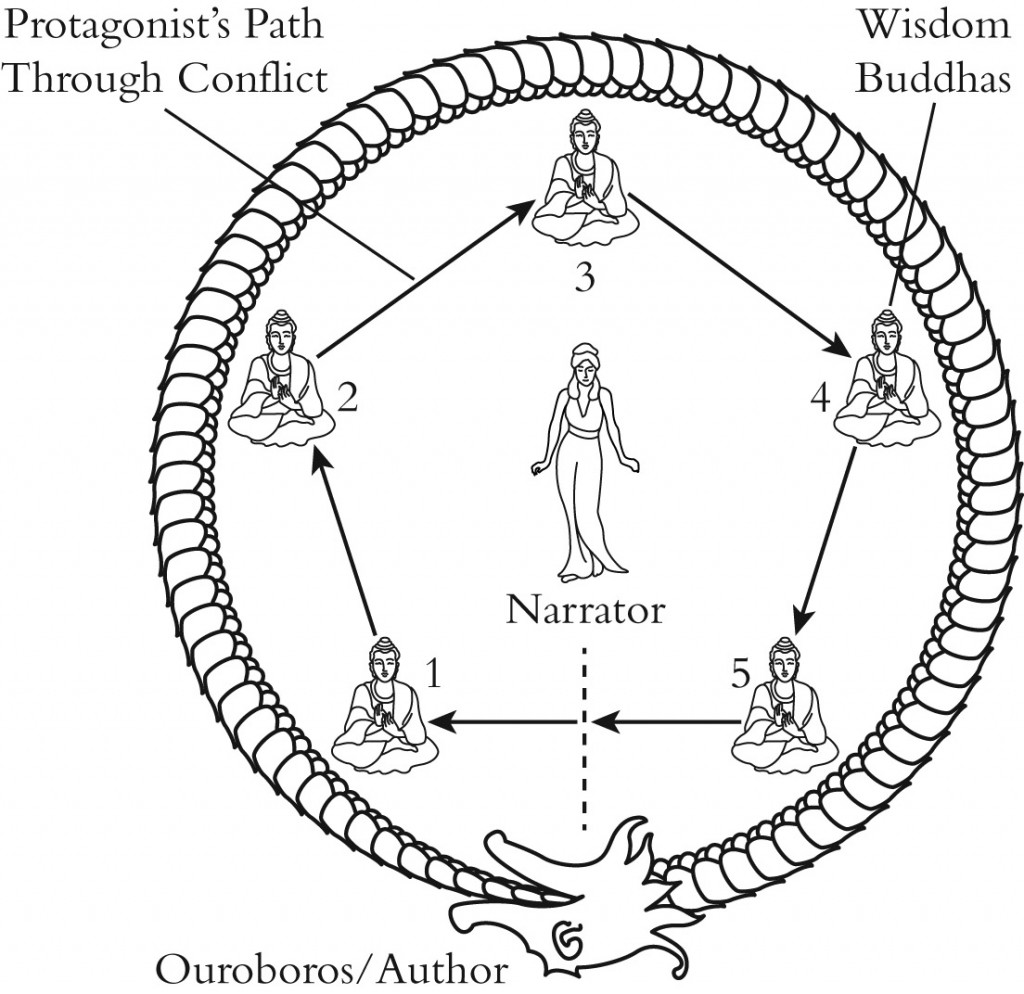

This diagram defines the different phases, plot points 1-5, through which the conflict must pass before it can be successfully resolved. Of course, the characters (protagonist and antagonist) experience not just the conflict but also the central theme, which is what the conflict is over. The protagonist experiences theme during the conflict, and it also evolves along the same lines as that conflict. This evolution is defined by what I call the Five Types of Deep Awareness, as shown in the following graphic, where each wisdom (replacing the plot points in the plot pentagon) is represented by a Buddha:

The protagonist’s relationship with the theme results in enlightenment that enables her/him to either overcome, or succumb to, the antagonist. This relationship between conflict, character and theme is all contained within the story’s premise, or what I call the prima materia in Story Alchemy. See Chapter 2. It also describes what that dragon circling the Buddhas represents.

As stated in the Wikipedia quote above, we have other uses for the word “theme” as it applies to stories, and these uses are more limited and less defined. For example, Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby uses the colors green and gold frequently and is specific enough that we realize that they are “themes” in the story but in a more limited sense. They have a connection to “greenback” and the expensive and fashionable metal, and also imply something about the central theme, which concerns the American Dream. Gatsby has a huge library but has never read any of the books. He claims to be an “Oxford man” but has never actually been to Oxford. He is very rich but apparently he got his money from being a drug dealer. We start to realize that the title The Great Gatsby is ironic. Gatsby is a fraud, a nobody. Or worse, a criminal. Ill-gotten gain is a theme in the story, and it has a supporting role to the central theme.